BOOKS/WRITERS

Mini-interview

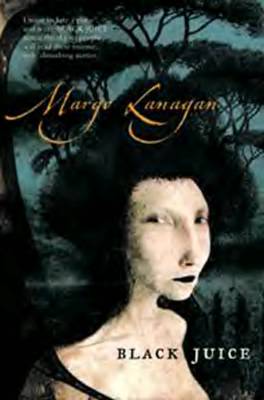

Margo Lanagan, novelist

I've written both short stories and full-length novels, but my last two books have been collections of short stories because I've been working full-time while putting them together, and haven't had the kind of time I need to be able to keep a novel in my head.

THE LONG AND SHORT OF IT

If there are [restrictions involved in writing in a condensed form], I don't feel them as restrictions -- I quite like plunging into a story right up close to the climax, and creating worlds that hold together juussst long enough to get the most out of that moment of character transformation.

Also, only having time to suggest setting, rather than being obliged to construct and present a created world right down to the plumbing, means that I get all the fun of a novel but without the responsibility!

However, after a while of writing short stories, I do hunger to be working on something bigger (and I actually am, at the moment), so that I can slowly build a story with lots of different intertwining pieces that come together in a more

multi-layered way at the end.

Also, making more complex characters with proper histories, and tracking their development and changes, is rewarding.

THEMES

Themes that come up again and again: Grief, aloneness/loneliness, being surprised by the world's strangeness, finding a place for yourself in the world, finding ways to be hopeful, how families work (particularly mothers), how other kinds of groups work, how different people deal with emotional crises.

I think I only know what themes I'm exploring in retrospect -- the thematic stuff tends to happen subconsciously.

When I'm writing, I'm focusing on the strangeness of the world I'm creating, or getting to know the characters and moving them through the plot.

When I get to the end, or sometimes quite a while afterwards, I'll realize that I've written a disguised memoir, or actually been writing about motherhood when I thought the child was the main character.

This doesn't quite answer your question, though. I guess these themes are related to my daily-life preoccupations, as well as to past experiences that have left their stamp on me.

I certainly don't consciously go in thinking “It's time people paid more attention to the amount of emotional work mothers do!” -- it's not a proselytizing thing.

But most of my stories, however much I think I'm exploring new territory when I'm writing them, will end up addressing one of these themes.

The more I think about this question, the more I think it requires a certain amount of therapy to answer...

ART BLOCKS

The story "Wooden Bride" in "Black Juice" was difficult to finish, because the story was based on a dream I'd had, and I wanted to put in the happy girl-meets-boy ending that I'd had in the dream.

I created the boy several different ways, but I just couldn't get him to behave with the same calm, romantic charisma he'd had in my dream.

In the end the girl just had to get her reward from having made it to the church on time (the ceremony was more a confirmation, a sort of rite of passage, than an actual wedding) instead of finding love as well.

Of course, there have been a fair few stories that were so difficult they didn't get finished at all -- generally this is because I've imagined a character but not thought sufficiently about how that character is going to be challenged by circumstances, or I've created characters that I don't particularly want to spend much time with!

My personal favorite: This is a hard question! I think "Singing My Sister Down" is one of my favorites in "Black Juice"; and in "White Time," "The Night Lily" -- and I think I like them best because I hardly know where they come from in myself, and they can mean several different things.

They're still puzzles to me, whereas other stories in both collections are laid out flat like a map and I can see exactly what they're saying and how they work.

These two are the ones that surprised me, which probably means that I was in a very relaxed state when I wrote them, not feeling self-conscious or anxious about them.

Both stories' prose have also been pared back to the bone -- I really feel there are no wasted words with either of them, which I like. I like a nice, lean story.

ABOUT: “WHITE TIME”

"White Time" is the title of the most YA story in the book, about a girl who does a stint of work experience in a government white-time laboratory.

White time is like white noise, all times at once, and occurs in reservoirs all through the universe.

As species evolve and pass through the various phases of learning about time travel, they always pass through the stage where they get their coordinates wrong and end up floating in white time.

Humans (who have of course learned to time travel perfectly!) take on the task of moving them out of the reservoirs either on to where they wanted to go, or back to where they came from.

ABOUT: “BLACK JUICE”

Black Juice was my older son's name for Coca-Cola when he was little.

I was looking for something black, to make a companion title to “White Time.” But also, the stories in “Black Juice” were written during a fairly dire period in my life, so the title also makes sense as an indicator that the book is squeezed out of dark times.

The next collection will be called “Red Jam,” which has the same kind of innocent-appearance-disguising-ew-factor as “Black Juice.”

READING, THE EXPERIENCE

I think the stories say what I'd like them to understand better than any comment I can give about them. These stories are being marketed as young adult fiction, but I'd like parents to understand that they're not children's stories -- heck, I'd like parents to read them themselves!

As to what readers get out of them, I'd like readers to be knocked sideways. These stories are pretty intense, and lots of readers have said they can only read one in a sitting -- then they have to go away and recover for a while.

I like the idea that they make people think, that they blow people out of their normal way of reading, that you can't rush them.

COMING UP

I've nearly finished first-drafting the stories in the next collection, “Red Jam,” which is very much the same type of science fiction/fantasy/horror mix as “White Time” and “Black Juice.”

I'm also rewriting the first novel of a YA fantasy quartet, which I hope to complete the remaining three volumes of in 2005. Right now I'm taking some time off from full-time employment as a technical writer, and being a full-time fiction writer, which is just paradise -- only trying to cram three lives into one, instead of four!

Bio: Margo Lanagan has published poetry, YA novels and short stories for science fiction, fantasy and horror fans.

Her books have been Aurealis Award winners, and been shortlisted for the Ditmar Awards and the New South Wales and Queensland Premier's Literary Awards.

Her short-story collection "Black Juice" won a Victorian Premier's Literary Award, and stories from previous collection, "White Time," were selected for inclusion in several Year's Best (and in one case, half-century's best) anthologies. Lanagan lives in Sydney, Australia.

Interested in learning more about this author? Lanagan was recently a guest author at Torley’s/Parrish’s Patch. Find out more, here.

Find more books/writers content in the DEC/JAN issue of "Arte Six."

BOOKS/WRITERS

Excerpt from “Black Juice”

In "Black Juice," Lanagan delivers ten unusual stories that intrigue, shock, delight and move the reader to tears with their imaginative reach, their complexity, unpredictability, subtlety and humanity.

From: “Sweet Pippit”

We set out in the depth of night, having held ourselves still all evening. Hloorobnool was poor at stillness, being only in her fifties, but our minder was a new man; he likely thought she rocked and puffed and raised her trunk like that every sunset.

We could all have reared up and trumpeted, no doubt, without alarming that one. But our suffering was close to the surface; better to keep it packed into a tight circle than to risk rampage and shooting by letting it show.

With the man gone to his rest, Booroondoonhooroboom set to work. She used her broken tusk on the gateposts, on the weak places where the hinges had been reset after Gorrlubnu’s madness. Pieces pattered to the ground softly as impala dung.

She worked and she sang, drawing the lullaby up around us. Before long we were all swaying in our night-stances, watching Booroondoon with our ears and our foreheads as well as our eyes.

And then she had done loosening. "Gooroloomboon," she said, and Gooroloom came forward. The two of them lifted aside the chained-together gates, and there between the gateposts was a marvellous wide space.

We had not expected it, somehow -- though had we not all said, and planned, and agreed?

Ah, it is a difficult thing, the new, and none of us like it much. We swayed and regarded the open gate.

We were used at the most to circling, with an owda on our back full of tickling peeple, and our mahout on our head.

It took Booroondoon, our queen and mother, still singing very low, to move into the space, to show us that bodies such as ours could move from home into the dark beyond. And as soon as the darkness threatened to take her, to curtain her from our sight, it became not possible for any of us to stay.

And so we moved, unweighted, from the gardens; Hmoorolubnu took my tail, as if that small thing would hold her steady in this storm of freedom. Zebu choked at us behind their rails, and a goat on the stone hill lifted its head and gave brittle cry.

But our bearing is the sort that soothes others; we move with inevitability, as the stars do, as the moon swells and shrinks upon the sky.

We brushed aside the wooden entry gate as if it were a plaything to be tossed aside, and the other animals remained calm.

Gooroloom tumbled the little office-box to sticks, and our feet crushed it to dust.

Above the dark and swelling river of our rage, my delight in our badness hung briefly bright.

His name was something like Pippit. It was too short for our ears to catch, as all peeple’s names are; twig-snaps and bird-cheeps, they finish before they properly start. But his smell was a lasting thing, and his hand.

Pippit of all peeple could tell badness from goodness, as we could. He would know that this was our only choice, he who could still our feet with a word, whose slender murmuring soothed us when all other voices were pitched too high and madding, who slept among our feet and rode us without spear or switch -- whom we missed in a rage of missing, ever since he had been taken from us to somewhere in this dark out-world.

Gooroloomboon spoke through her forehead, wonderingly: "How our minds have become circle-shaped, from all our circling, squared from pacing that square! Once we were wild! But I fear I have no wildness any more, Booroondoon; maybe wildness has died in my blood and my feet can move only in circle and square. What are we to do for water and for food, mother? And how are we to know where to find our sweet Pippit? And if he be in a place that requires some badness to reach him, can we do such a thing, even in his name?"

Booroondoon, her graciousness, heard Gooroloom out. "Put away your fears," she said, even as she lullabied. "Fears are for little-hearts, or the lion-hunted. I have never been wild in my life, yet our Pippit’s track through this world is as clear as a stripe of water thrown across a dry riverbank. What you love this much, you can always find again."

And our spirits, which had been poised to sink with Gooroloom’s worry, lifted as if Booroondoon’s words were buoyant water, as if her song were breeze and we were wafted feathers.

We walked out among peeple’s houses, that were like friends standing beside the path.

With every sleeping house we passed I was more wakeful; with every step I took that was not circle-path, or earth we had trodden as many times as there are stars, something else broke open in me.

My mind seemed a great wonderland, largely unexplored, my body a vast possibility of movements, in any direction, all new.

There would be food and water, good and bad, all new -- Gooroloom would smell them, too, when she finished fretting. I wanted to lift my head and trumpet, but there was joy also in knowing I must not, in moving with my fellows through the sleeping town, making no sound but planting feet and rubbing skin and the breath of walking free.

We came to the town’s edge. Without pausing, Booroondoon continued on under the moon towards nothing, only parasol trees that cannot be eaten, only a line that had stars above it, dry shadows below.

We followed, and the town smells fell behind. Hloorobn, ahead of me, lifted her trunk. I head-bunted her rump, to keep her quiet, and she grunted low in surprise.

Then we settled to a strong pace after Booroondoon, rolling our yearning rage out onto the plain.

Excerpted from "Black Juice" (Dec. 2004, Allen and Unwin Australia)

© 2004, Margo Lanagan. All rights reserved. Used with permission.

Read more books/writers content in the DEC/JAN issue of "Arte Six."

<< Home